Recently, when I was out at the famous outdoor squash court in Maspeth, New York, Robert Gibraltar kindly gave me a rare copy of the 1991 U.S. Open program.

The 1991 Open, as it was for a decade and a half, was directed by Hazel White Jones and Tom Jones. They held it in October 1991 on a portable court on the indoor tennis court at the Heights Casino in Brooklyn. The official title was the Pierce Leahy U.S. Open—the event was generously sponsored by the squash-playing Pierce family. The family has been central supporters of squash in America ever since, including the Pierce Family U.S. Squash Hall of Fame at the Arlen Specter US Squash Center.

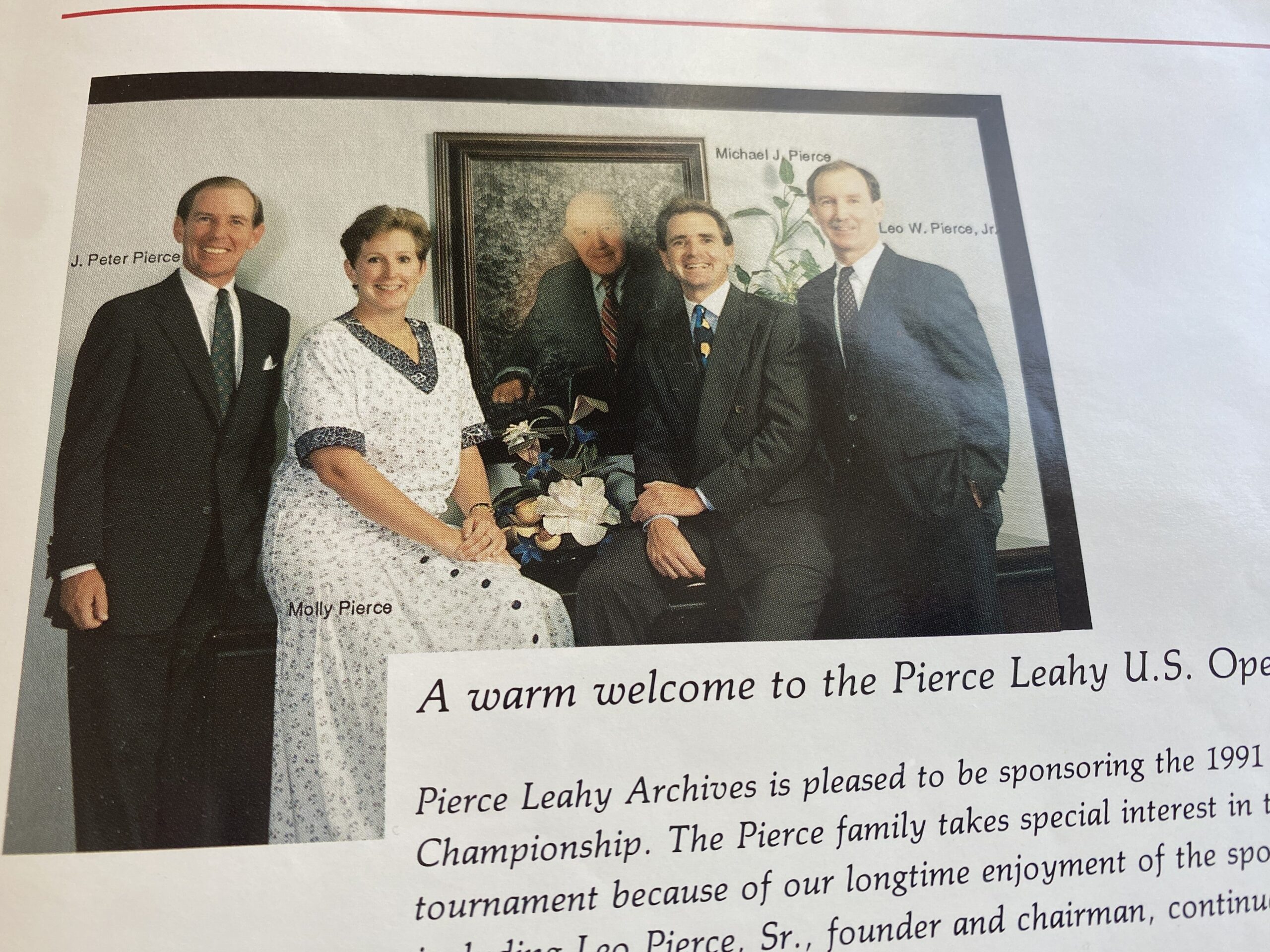

Here is an ad from the program:

The 1991 Open was men only (the women’s draw started two years later); thirty-two in the qualies which Jody Larson helped host at Uptown, and twenty-four in the main draw; and $60,000 prize money (the equivalent of $139,000 today).

The thirty-three year-old program had a few other fascinating tidbits.

*Olympics: IOC president Juan Samaranch visited the 1990 Spanish Open—perhaps we had a better shot getting into the 1992 Barcelona Games than we thought?

*Refereeing: The 1991 Open was refereed and marked entirely by the players before or after their own matches. Shaun Moxham was the tournament’s head referee. The Australian, who was then based in Boca Raton, Fla, coordinated the officiating assignments and refereed the semis and finals himself. Today Moxham has a burgeoning squash facility network called MSquash. He claims the M references mindset, movement and match strategy. Perhaps it’s also a reminder of the 1991 Open, as in “I MOST definitely do not want to do that again?”

*The official racquet of the 1991 Open was Estusa. The Taiwanese brand was briefly at its height in the early 1990s. Jahangir Khan was using their squash racquet and both Boris Becker and Jimmy Connors played with their tennis racquet. Connors, the month before, had used a neon yellow Estusa racquet during his notorious run to the semis of the US Open at the age of thirty-nine. All those images of Connors fist-pumping with one hand—in the other is a Estusa bat. Today, Estusa are among the rarest of collectible squash racquets